Guest Post by Emily Jackson

January 15, 2015

This article first appeared in the January 2015 edition of NCMJ;76(1):54-56 which can be accessed here: http://www.ncmedicaljournal.com/archives/?76115

Whether it is linking farmers with buyers or teaching children about vegetables growing in a school garden, connecting people to the source of their food is a vital part of building rural food systems that are healthy food systems.

America is in the midst of a health crisis, with chronic diet-related illnesses like diabetes and obesity plaguing the nation. The problem is worse for rural Americans, as the prevalence of obesity is markedly higher among rural populations [1]. Rural communities sometimes lack access to the resources available in urban communities, but they also have access to unique opportunities to promote community health and reduce rates of chronic disease.

Rural Assets: Community and Local Food

While residents from rural communities often find themselves at a disadvantage compared to their urban counterparts when it comes to healthy eating and opportunities for physical activity, in some ways rural communities have distinct advantages. Community is one of the greatest assets of rural places. Close-knit ties can bring residents together for the common good. In addition, rural residents typically lack the luxury of acting in silos; instead they must wear many hats. This enables cross-sector work to happen naturally, which is crucial for developing healthy community strategies.

Coupled with the community spirit of rural communities, agriculture and local food are also important resources. Local food from local farms can provide communities with a wide variety of fresh fruits, fresh vegetables, and lean proteins, all of which are staples of a healthy diet. By tapping into a natural extension of rural communities—their farms—local food systems can be developed in rural communities, and these systems can be a sustainable and effective way of building health in rural areas.

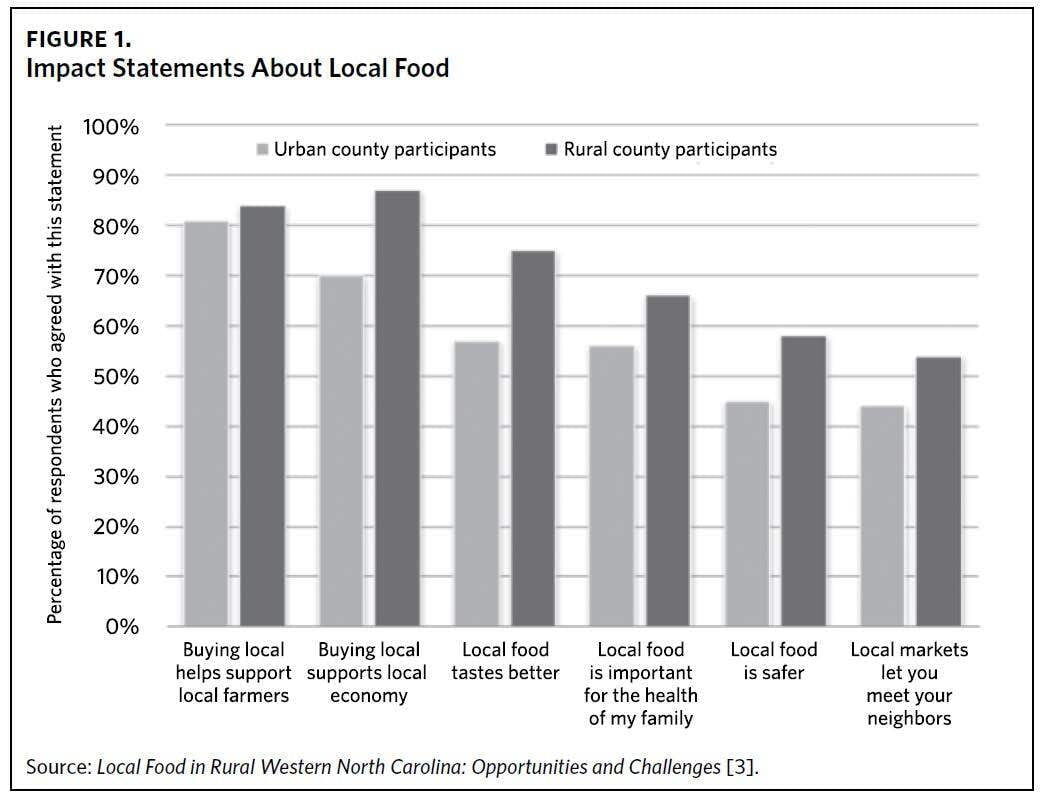

Eating local food, which is now more than a trend and is on its way to being a full-fledged movement, is showing great promise in mitigating some of the barriers faced by rural communities (in particular, lack of access to healthy food). Increasingly, consumers are interested in knowing where their food comes from and who grew it, and they are often willing to pay more for a local product (See Figure 1) [2].

Numbers and Connections

According to the US Department of Agriculture, local food sales have increased from $1 billion in 2005 to $7 billion in 2012 [3]. According to a recent analysis conducted by the Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project (ASAP), farm direct sales alone have increased by 70% in Western North Carolina counties (from less than $5 million in 2007 to over $8 million in 2012) [4]. This growth is even more impressive when compared to the rest of North Carolina (removing the 23 westernmost counties in the state), which experienced a net decrease in farm direct sales. Over the past 10 years, counties in Western North Carolina have seen increased interest in local food across the board, including increases in farmers’ markets, community-supported agriculture, and farm tourism; greater use of locally grown food by schools, hospitals, and universities; and more purchasing from local farms by restaurants and grocers.

What is important about these increases is more than numbers; it is also about making connections. Whether it is connecting farmers with buyers, connecting a child with vegetables growing in a school garden, or the connections families can make while on a farm tour, connecting (or reconnecting) people to the source of their food is a vital part of building rural food systems that are healthy food systems. These connections, while not limited to rural areas, are certainly enhanced by the rural environment.

After almost 2 decades of working to improve the local food system in Western North Carolina and the Southern Appalachians, ASAP has come to one basic conclusion: we need more individuals, families, and children to have connections to their food. Although the local food movement is growing, too few of us know about the food we eat—where it grows, who grows and harvests it, how it is grown and processed, how it benefits our health, or the impact of our food choices on the world around us.

Children and Local Food

Two key strategies to address childhood obesity in rural communities are to engage and educate families about healthy eating and physical activity and to establish farm-to-school programs [5]. These strategies have been key program activities in ASAP’s Growing Minds Farm to School program since 2002.

ASAP defines the farm-to-school program as having 4 components: edible school gardens, farm field trips, classroom cooking (featuring locally grown products), and the serving of local food in the cafeteria. The farm-to-school program also includes the preschool setting, since attitudes and behaviors about healthy food are often established at a young age.

Currently the majority of farm-to-school and farm-to-preschool programs across the country focus primarily on procurement (ie, local products being served in the cafeteria). ASAP has taken a different approach. Children are much more likely to consume local produce served to them if they already have a connection to this food. Experiences such as tending to the school garden, milking a cow on a local farm, or cooking with local food in the classroom help give children this connection. Given this focus, ASAP considers the local procurement piece to be the last component that should be adopted as part of a farm-to-school program.

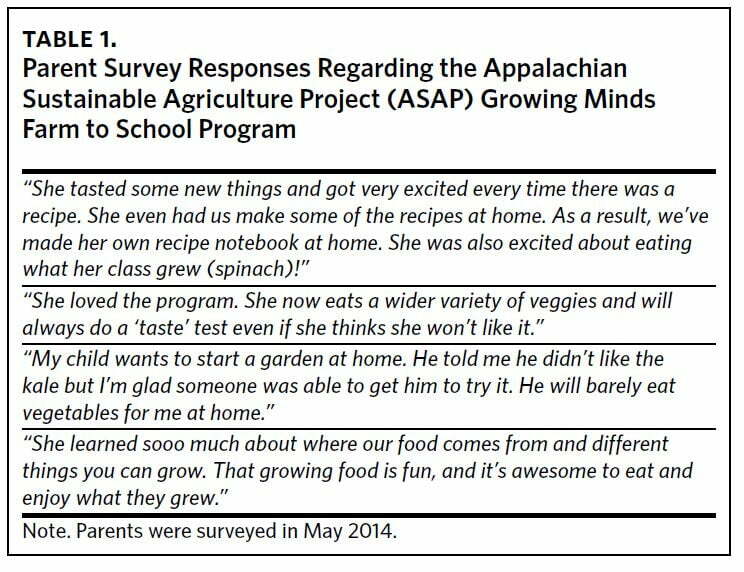

In much the same way that lessons about recycling, smoking, and drug use went home from schools and affected family life, farm-to-school programming promises to change family dynamics as well. This is evident in the farm-to-school program at Cullowhee Valley School, an elementary and middle school in rural Jackson County. In this program, students received an average of 6 farm-to-school interventions per month. Each child from prekindergarten to 2nd grade was involved in a weekly cafeteria taste test (of a local product), a monthly classroom cooking lesson, and a monthly school garden experience. Judging from parent survey responses, farm-to-school experiences are making a difference in the lives of these children and their families (See Table 1) [6].

One question that is often raised is whether children in rural communities know where their food comes from. It would seem reasonable that they would, but too often children today (rural and urban alike) are at least 1 generation removed from how food is grown. If children make any reference to farming or gardening, it is usually attributed to their grandparents, not their parents. This means that it is not just our children who are disconnected from their food; most adults are as well. In addition to having lost the skills to grow our own food, we also lack food preparation skills, which leads to an over-reliance on processed and ready-to-eat foods.

Fortunately, children generally enjoy cooking and tasting fresh, locally grown foods; they appreciate time in a school garden; and they welcome an opportunity to visit a local farm. Many adults, on the other hand, have grown up with a taste for fat, sugar, and salt; lack cooking skills and the inclination to cook; and do not necessarily place value on local food and farms. In response, ASAP has focused attention on adults, understanding that in order for children to enjoy the hands-on experiences of cooking, gardening, and farm visits, we must first make the benefits of these experiences clear to adults. Teachers, school nutrition staff, and parents need to have experiences of their own to understand their significance.

Upstream Approach

Since 2009, ASAP has taken this focus on adults one step further. Rather than just rely on classroom teachers or school nutrition staff to understand our philosophy, ASAP has ventured upstream. With initial and current funding from the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina Foundation, ASAP—in collaboration with Western Carolina University, Lenoir-Rhyne University, Jackson County Public Schools, and Mountain Projects, Inc.—has implemented the Growing Minds @ University (GM@U) project. GM@U integrates local food experiences and training into undergraduate and graduate curricula for education students, nutrition and dietetics students, and dietetic interns [7]. This training and experience with local food build the capacity of future teachers, registered dietitians, and health professionals to incorporate local food and farm-based experiences into their work. These undergraduate and graduate students not only learn about local food and farm-to-school programs in the university classroom setting, they are also provided with experiences in schools and preschools. Here they get to see firsthand that children are willing to try new vegetables, that teachers can integrate farm-to-school programs into the curriculum, and that school gardens are wonderfully engaging learning environments.

Most importantly, these students are gaining an understanding of how and why they could utilize local food and farm-based experiences in their future professional careers, thus helping their future students or patients to make connections to the source of their food. One way the project’s impact is assessed is through student reflection forms. On one such form, a health science student at Western Carolina University said, “[GM@U] will have a huge impact no matter what field in nutrition I go into. Eating local and supporting your community is so important no matter where you are!” Our local communities are already experiencing the benefits of the GM@U project; graduates of the program have taken positions in university food service and are creating new jobs (such as a food truck business that incorporates local food), thus helping to change food environments for the better.

ASAP’s Theory of Change

ASAP’s theory of change is that localizing food systems strengthens local economies, boosts farm profitability, increases sustainable production practices, and improves individual and public health. This theory is grounded in ASAP’s conviction that when the distance between consumer and producer decreases, transparency in the food system increases, which in turn drives changes that increase public health, build local economies, and sustain family farms. ASAP believes that we must rebuild our lost connection to food and must understand the impact of our food choices.

We are now at the beginning of a social movement that will transform our food system. This movement has the potential to empower us to create a food system that is equitable, environmentally sustainable, economically viable, and health promoting. As Wendell Berry noted, “eating is an agricultural act.” It is also a political one—an act of democracy that can change our food system.

Acknowledgments

Financial support. Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project receives support from the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina Foundation.

Potential conflicts of interest. E.J. has no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. Befort CA, Nazir N, Perri MG. Prevalence of obesity among adults from rural and urban areas of the United States: findings from NHANES (2005–2008). J Rural Health. 2012;28(4):392-397.

2. Research Inc. Consumer Behavior Research. Asheville, NC: Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project; 2014.

3. Jackson C. Local Food in Rural Western North Carolina: Opportunities and Challenges. Asheville, NC: Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project; 2013.

http://growing-minds.org/documents/local-food-in-rural-wnc-opportunities-and-challenges.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2014.

4. USDA celebrates National Farmers Market Week, August 4–10 [news release]. United States Department of Agriculture website.

http://www.usda.gov/wps/portal/usda/usdamediafb?contentid=2013/08/0155.xml&printable=true&contentidonly=true. Published August 5, 2013. Accessed October 10, 2014.

5. Local food sales surge in WNC [news release]. Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project website. https://asapconnections.org/front-page-posts/local-food-sales-surge-wnc/. Published May 2, 2014. Accessed October 10, 2014.

6. Nemours. Childhood Obesity Prevention Strategies for Rural Communities. Jacksonville, FL: Nemours; 2014.

http://www.nemours.org/content/dam/nemours/wwwv2/filebox/service/healthy-living/growuphealthy/nhps/Childhood%20Obesity%20Prevention%20Strategies%20for%20Rural%20Communities.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2014.

7. Paxton-Aiken A, Jackson E, Littman A, Robison S. Local Food and Farm to School Education Project: Supporting Nutrition and Dietetic Student Achievement of Core Knowledge and Competencies Through Local Food-Focused Service-Learning Opportunities. Hunger and Environmental Nutrition Newsletter. Chicago IL: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2013. http://growing-minds.org/documents/hen-article.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2014.