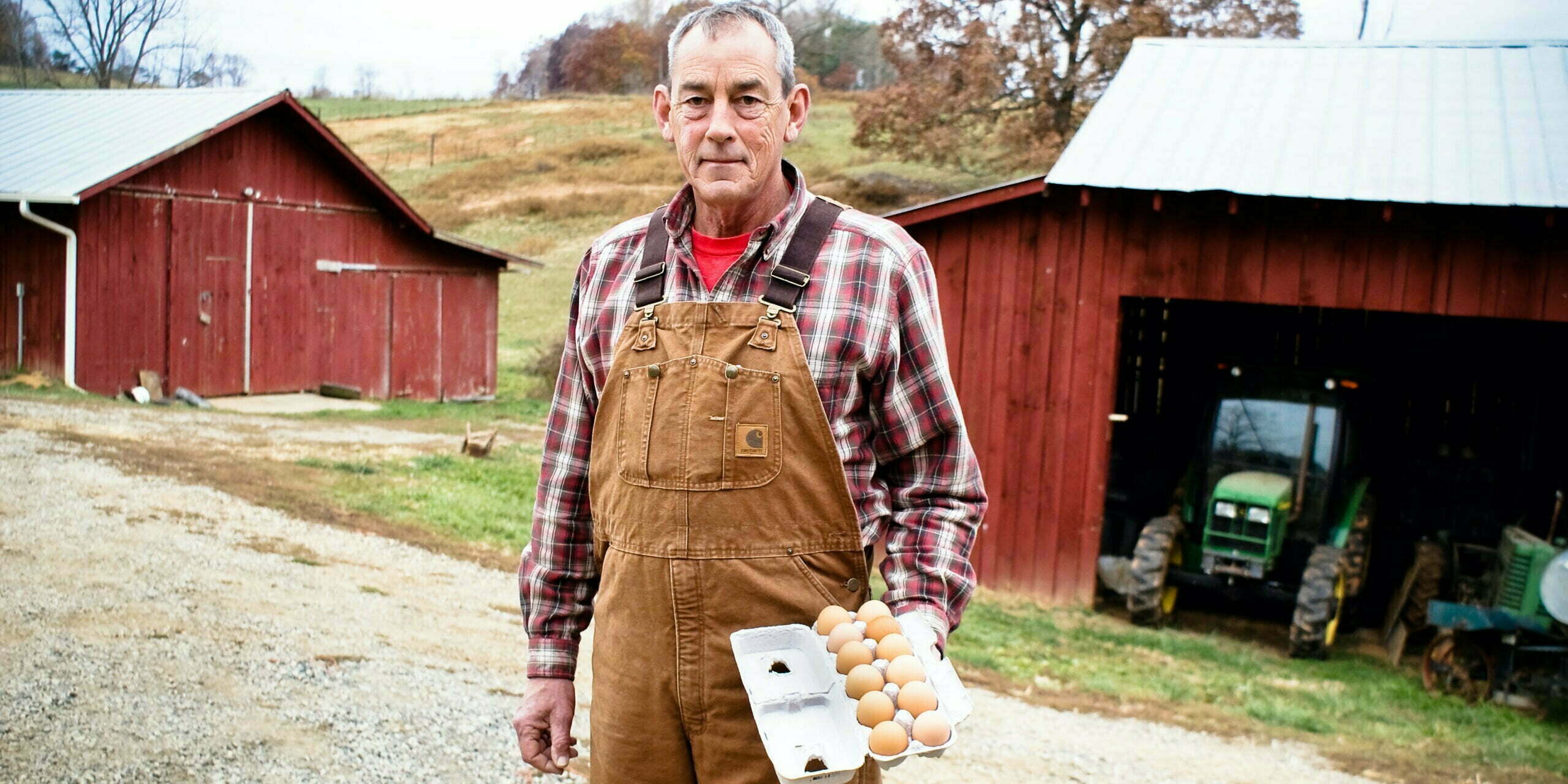

“I’ve just always wanted to farm since I was a child,” says Mike Brown, owner of Farside Farms in Buncombe County, NC. “My grandfather in Virginia farmed, and I guess that’s kind of where I got bitten by the bug when I was little.”

Brown has now been farming in Western North Carolina for five decades, beginning in the 1970s. He’s witnessed dramatic changes in the region, including the transition away from tobacco, the loss of farmland to development, and the evolution of Asheville from a sleepy mountain town to a booming food destination.

Throughout those years, Brown explored various market outlets as he adapted to the changing agricultural environment. He got his start cultivating burley tobacco along with other commodity crops. The early years of tobacco were quite profitable.

“I bought the farm where I am now in, oh, 1990,” he recalls. “And tobacco paid the payments.”

He attributes his staying power as a farmer to his ability to purchase that land outright, and then to only expand as money allowed. “I built chicken houses over a period from 1996 to 2009. Every four or five years, when I got financially able, I built a new chicken house.” He was also able to purchase his grandfather’s farm in Virginia.

By the time the tobacco buyout came in 2004, Brown was transitioning to vegetables and eggs. He initially sold wholesale through a packing house in Hendersonville, but soon realized he would be better off with direct sales.

“I was selling vegetables through the broker and you just didn’t get anything for them. I mean, they just didn’t pay. I sat down and did the math. I could go straight to retail and cut the middleman out and grow two-thirds and still make as much money.”

He bought two farm stands in North and East Asheville and started selling directly to customers. Eventually, his primary product shifted to cage-free eggs.

Meanwhile, a chance meeting led to another way Brown could differentiate his products. Everyone knows you should never bring up politics at the dinner table, but less commonly understood is that talking about dinner—or in this case food production—at a political rally can be productive. At least that was the case when Brown met ASAP’s founder, Charlie Jackson, in the mid 2000s at a gathering to support a candidate for the North Carolina Commissioner of Agriculture. Jackson convinced Brown to adopt ASAP’s new Appalachian Grown™ branding.

“I was one of the first ones to latch on to the Appalachian Grown label and have it put on my boxes and egg cartons. It was really to my advantage when I did it.” Brown says the logo gave his customers the assurance they needed to trust that his product was local and fresh.

Currently, Brown has 3,000 laying hens and packs on average 200 dozen eggs a day. You can find them at Earth Fare, French Broad Food Co-op, and Hopey & Co., as well as restaurants like West End Bakery, Table, and Bargello.

But over the past 10 years Brown has been scaling back in preparation for retirement. He stopped growing vegetables when he sold the farm stores a few years back. During the nearly 15 years that he owned the stores, Brown says he watched his customer base trend to a younger generation seeking out locally sourced produce and goods.

“I know when I first opened, we had a lot of elderly older clientele. Then when I quit, it was a much younger clientele. The population in Asheville has definitely changed over.”

While he is most known for his fresh eggs and farm stands, Brown has been quietly carrying on the long tradition of Jersey cow dairies in the region. His herd, now managed by Mills River Creamery, are direct descendants of the cows owned by George Vanderbilt of the Biltmore Estate.

Farming is a seven-day-a-week job, and Brown is looking forward to retirement. Chuckling, he says he’s looking forward to sitting on the porch and watching someone else do the work for a while.