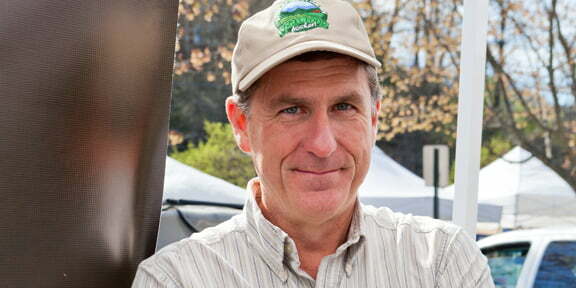

ASAP founder Charlie Jackson is retiring this month. For our Faces of Local interview, we asked him about what led him to farming in Western North Carolina and the organization’s early days. (Read more about ASAP’s history and agriculture in WNC here.)

Where were you before ASAP?

I was in grad school in Maine and worked with somebody named Helen Nearing. She and her husband, Scott, had inspired a lot of the Back to the Land movement in the ’70s. I was inspired by that and moved back to North Carolina, to Madison County. I was trying to farm. It was tough—not the farming part but the selling part. Asheville was sparsely populated, boarded up. There were no restaurants. It was not a place where you would sell your products. A group of farmers came together and formed Mountain Organic Growers. The idea was that in Western North Carolina we had different seasons from the rest of state. Together we could grow things up here and then ship them down the mountain and have a bigger market. It barely worked. It was logistically expensive. The value of organics wasn’t quite what it needed to be. That eventually became Carolina Organic Growers, which was really an early food hub before food hubs were a thing. Then the French Broad Food Co-op opened a farmers market and we sold there. But I wasn’t making a living farming. I was doing carpentry as well. Emily was working in domestic violence shelters. We weren’t making money. We were renting land, and we were never going to own land.

What was the agricultural environment here?

This was the mid-’90s and tobacco was king. But the Back to the Land movement had brought a lot of new people to Western North Carolina in the ’70s who were doing alternative agriculture. A lot were growing pot out in these rural communities. Really, the intersection of tobacco, growing pot, and Back to the Land has a lot to do with where we are now in local food movement. Tobacco had kept farmers farming on small plots of land, but was on its way out. There was a big crackdown on pot growing in the mid ’90s, so we were losing two cash crops. Most people are aware of tobacco, but the other is more forgotten. There was a vacuum and at the same time there was this influx of new people and new ideas.

And ASAP formed in that vacuum?

There aren’t models for what ASAP is. We didn’t know it could be a thing. I convened a group of farmers in Madison County, realizing we were vulnerable. It was some old timers, but mostly new timers. Tobacco was the thing we really had to do something about. We didn’t know it at the time, but seven years later, tobacco would be gone from the region. Local food wasn’t the first thing that came out of this. We looked at transitioning tobacco into organic and farmland preservation. Right at the beginning, in ’95, we did a listening project. A lot of volunteers got trained in how to conduct community interviews, what they saw as challenges, opportunities, what they valued. It was a really good way to get into conversations across generations, families, the from heres and the come heres. People really valued the culture and quality of life in their communities. They liked tobacco because it was steady and seasonal, and those rhythms were valuable. What came through was that they wanted to keep not tobacco but that kind of life.

Probably what moved us forward as an organization was the Master Settlement Agreement [in 1998] that created the Golden Leaf Foundation and North Carolina Tobacco Trust. That legitimized what were doing and backed it up with some money. In 1995 to 2000 nobody was getting paid. We were all just doing it because we wanted to see this change. There was no reason to think we could create an organization and survive. It was stupidity, but I really wanted to do something other than carpentry on the side. I said I’m willing to put in a couple of years to see if we can do something with this. These funds brought opportunity at a whole other scale than we could have imagined. So [in 2002] we formed a board, filed the papers, and signed them outside in a parking lot.

When did it become about local food?

Around 2000, both with new resources and new ideas, the thing that really took off and resonated was a local food campaign. At the time it was kind of a radical idea. We were just in a generation that had lost connection with food. It wasn’t something people thought about. There wasn’t a place to get it. The French Broad Food Co-op farmers market had three vendors. The North Asheville Tailgate Market was a different kind of market, not what we have today. There was The Market Place with Mark Rosenstein, but otherwise not a lot of restaurants. Then a lot of new things started happening at the same time. The TDA was beginning to promote Asheville as a destination. Restaurants were opening and distinguishing themselves with the quality of ingredients they were able to get. Creative chefs were embracing that. The volume of production was going up, and folks started opening up farmers markets.

One of our early purchases, which was a really big deal at the time, was a digital camera. I would go out to markets and take pictures and I developed a relationship with the Citizen Times. Polly McDaniel was the features editor, and she said, sure, we’ll print a weekly market report. We were scraping by and that took us to a different place of legitimacy. The bumper sticker was guerilla marketing. We didn’t realize it at the time, but I look back and think how great. It was just a real expression of what people were wanting to participate in and support.

Local food is not a hard case to make—supporting the landscape and our ability to produce food, building community though eating the best food. But the next question would be, “How do I get it?” It wasn’t easy to find. Prior to the Local Food Guide as it is now, we would hand out sheets, printed on a copier. One side would be farmers markets and one would be CSAs. There had been guides to organic farms that other organizations in the state had done. For a lot of reasons, we wanted this guide to be broad. There wasn’t enough organic, for one thing. It was expensive and out of reach for farmers to produce and consumers to buy. Meeting people where they were was part of the mission we were developing. That’s why it’s called the Local Food Guide instead of organic.

Where did the name ASAP come from?

It was a clever acronym. In ’95 we were Mountain Partners in Agriculture. ASAP—Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project—was a project, essentially the Local Food Campaign. But that’s what we became as an organization, while Mountain Partners still existed as a bigger umbrella that included organic production and land preservation. We’ve had all kinds of issues with the name over the years. It’s hard to be big tent, open door organization if you have a word that’s been used as a weapon to demonize people. The word sustainable has evolved since then.

How did all of this fit into the national landscape?

As far as I’m concerned, the beginning of local food movement was Food Roots. The Kellogg Foundation was really important and unique at the time in looking broadly at food systems. They supported an effort called Food Roots, which brought together 10 groups from around the country to spend two years diving into this emerging idea of community-based food systems. The fact that we were chosen and got to take part was great, because we were not anything yet. There were more prominent groups from across the country, but we were all really pioneers. Things came out of that, like what a Local Food Guide would be, what a Local Food Campaign would be, how do you maintain integrity of local when it’s in a retail environment. There were all of these ideas bubbling up nationally. Out of that mix came ideas about farm to school. Emily was teaching and she wanted a school garden. I connected with the Community Foundation of Western North Carolina, which has been a really important supporter. They provided some funding, which was really the beginning of farm to school in North Carolina.

It’s worth appreciating that we’ve been able to survive as long as we have and do all the thing that we’ve done. I’ve always understood this would be a long-term effort. It’s not just one project, despite our name, and then it’s done. It’s really a process, and that’s worked for more than 20 years.